Cage & Kaino: Pieces and Performances is an exhibition accompanied by rare live performances of the work of 20th-century composer John Cage and contemporary multimedia artist Glenn Kaino.

On View: May 8 - September 21, 2014

Influenced by Marcel Duchamp, Cage and Kaino each created works inspired by their fascination with chess. Cage’s classic 1968 Reunion performance uses chess play to spontaneously compose and conduct unique musical performances, while in Kaino’s 2007 Burning Boards event the chess pieces made of burning candles force thirty-two players to confront time and chance. Gallery visitors may play on a working replica of Cage’s Reunion chessboard or study Kaino’s One Hour Paintings, portraits of grandmasters that surround his monumental Learn to Win or You Will Take Losing for Granted chess board, which features pieces cast from the artist’s own hands.

Revolutionary twentieth-century composer John Cage and contemporary conceptual artist Glenn Kaino produce works that highlight the sense of community created by chess, especially when interwoven with music and art. Inspired by influential twentieth-century artist and chess master Marcel Duchamp, Cage and Kaino disrupt the conception of chess as a game of pure skill by interjecting chance and indeterminacy into their chess-based artworks. Both inventor-type creators, the two work seriously in visual arts, music production, and public performance and share a passion for new technologies, ranging from Cage’s mid-century integration of portable radios in musical performances to Kaino’s millennial creation and sharing of art and music through the internet. Through the medium of chess, they unite members of the artistic and musical communities with whom they most like to collaborate.

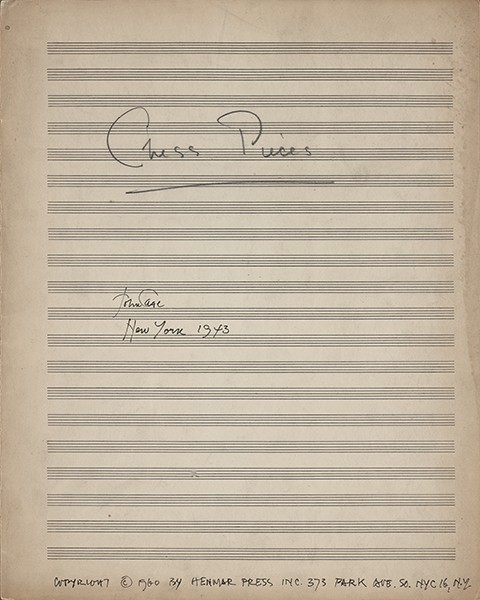

The son of an inventor, John Cage (1912–1992) expanded the notion of what sounds could be music and how music could be made. Declaring that “anywhere I listen can become a piece of music,”1 Cage experimented with Zen and chance operation to compose his music; the “prepared piano,” in which objects were placed on and under the strings of the instrument; and early electronic, often custom-made, instruments during live musical performances. In pieces like Reunion Cage was “…interested in music that isn’t written, and so, isn’t composed but simply performed…” with “…no barrier between what we’re doing and what you’re hearing.”2

Inspired in part by Cage, Glenn Kaino (b. 1972) has embraced the artistic possibilities of chess by challenging the conventional game structure and linear method of play. He transforms conventional materials and forms through a process of working that mobilizes the languages, logics, and economies of other creative disciplines as raw elements in artistic production. Kaino has been involved in major music, television, and digital media projects and has created various experimental platforms for the production and dissemination of contemporary art. He was the Chief Creative Officer of Napster and created the first online record label for Universal Music Group. Kaino co-founded both Favela, the first online destination for critical art discourse, and Deep River, an artist-run gallery in Los Angeles that was active through 2002, staging solo shows with some of the most important emerging artists in the city.

Teeny Duchamp, Marcel Duchamp, and John Cage

Ryerson Theatre, Toronto

March 5, 1968

Photo © Eldon Garnet

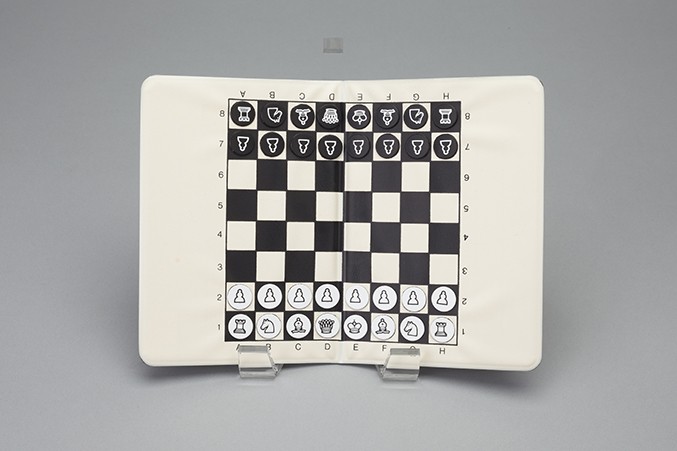

Performed on March 5, 1968, in Toronto, Canada, John Cage’s Reunion brought together the composer’s favorite creative partners to spend time indulging in his favorite activities—chess-playing and the creation of new musical forms. The production inaugurated Sightsoundsystems, the Toronto Festival of Arts and Technology, which celebrated experimental music. During Reunion, John Cage played chess against his friend, Marcel Duchamp, followed by his friend’s wife Alexina “Teeny” Duchamp, using an electronic chess board custom-designed for the performance by Lowell Cross, a Ph.D. candidate in electronic music at the University of Toronto. The players sat at a simple table and chairs in the center of the stage, evoking the informal environment of the Duchamps’ apartment, where Cage took chess lessons. Cage collaborated with four musicians, who performed electronic music using equipment located on four tables onstage. The electronic gear and skeins of wire running across the stage visually reflected the complexity of the music being created.

Cage organized Reunion using the principle of indeterminacy whereby “the performers are made co-creators of the work. Functioning independently of one another, each participant would enjoy a disciplined creative freedom within the specific parameters Cage arrived at through chance procedures. The performance would be created through ‘controlled non-control.’”3 At the event three composer/musician friends, Gordon Mumma, David Behrman and David Tudor, along with Lowell Cross, continuously sent electronic signals into the chess board, which, when randomly selected by a chess move, were then routed to any one of eight different speakers. As Cage and Duchamp competed, successive layers of sound advanced and receded producing “a unique performance that was spontaneous but not improvised, providing a surprise for performers and audience alike.”4 In twenty-five minutes, Duchamp, playing white and short a knight, defeated Cage, who then played against Teeny until the concert concluded.5 Cage re-staged Reunion on May 13, 1968, at Mills College, Oakland, California, playing against Lowell Cross; and again on May 27, at the Electric Circus in New York City, opposing John Kobler, an editor for the Saturday Evening Post. For the critics who caustically reviewed the series of concerts, Reunion may not have been a winning proposition. In his evaluation of the May 27 performance, New York Times reviewer Harold Schonberg said that Reunion was “lousy chess and lousy music.”6 Nevertheless, the piece was a conceptual and technological triumph that paved the way for later works exploring indeterminacy through the medium of chess.

Thirty-seven years after Cage’s Reunion performances, Kaino explored the game in his 2005 show titled Of Passed Pawns and Communicating Rooks, held at The Project, New York. The centerpiece of the show was Learn to Win or You Will Take Losing for Granted, which questions the meaning and value of winning and investigates the balance of conflict, cooperation, power, and promise among differing ethnic, racial and religious groups.

The piece, a monumental chess board composed of produce crates and ammunition boxes, represents a contested neighborhood or territory. The chess pieces are life-size cast bronze hands. One side, a “power” group, flashes hostile gestures while the other “promise” side offers peaceful signs, suggesting that either bonding or battle might soon ensue. “The promise side consists of the king in the classic ‘V’ peace sign, the queen, a ‘fingers crossed’ promise sign, the bishop, a ‘live long and prosper’ [sign] from Star Trek, the knight, a ‘shaka,’ or the Hawaiian sign for hang loose, the rook, a bent index finger referencing E.T. phoning home; and the pawn, a ‘thumbs up.’7 On the power side [the] king is a closed fist, the queen, a ‘gun,’ the bishop, the ‘middle finger,’ the knight, a L.A. gang ‘pitchfork’ sign, the rook, ‘the claw’ from kung fu films, and the pawn, a ‘noogie.’”8 Beneath the superficial differences, the opposing sides share something deeper in common: the fact that they were literally all cast from the same human hand—that of the artist. In his title, Kaino encourages winning, but the sculpture itself questions whether winning is best defined as the defeat of someone else or the reconciliation of opposing sides. “Take losing for granted” implies resignation–an acceptance that differences or difficulties cannot be resolved.

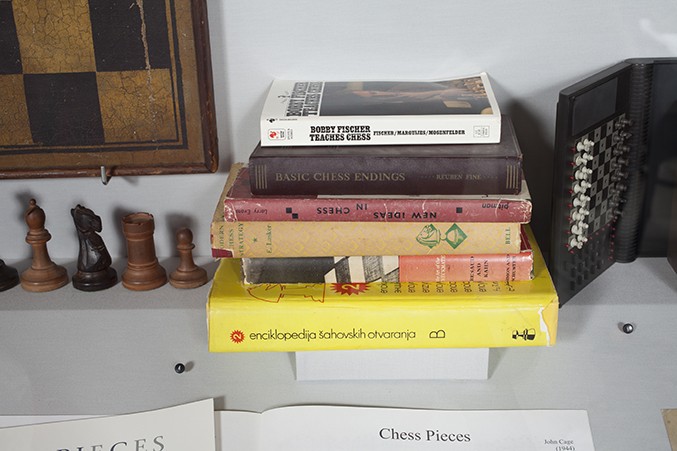

Kaino’s series of One Hour Paintings surrounded Learn to Win or You Will Take Losing for Granted in the installation. Timed by a chess clock, Kaino painted the silver-grey series of portraits depicting grandmasters past and present, male and female, young and old, each in only one hour. Including such diverse figures as Emanuel Lasker, José Raúl Capablanca, Bobby Fischer, Judit Polgar, and Xie Jun, they alternately suggest the audience awaiting an upcoming battle or chess’s extended family of mixed ethnicity reaching from the nineteenth century to contemporary times.

Glenn Kaino

The Burning Boards

Installation at the Whitney Museum of American Art at Altria, New York, 2007

Kaino again explored concepts of winning through the medium of chess in his 2007 performance The Burning Boards, developed for the Whitney Museum of American Art. As in Cage’s Reunion, Kaino uses the format of a chess competition to draw together friends from the worlds of art, chess, technology, and music. In the piece, thirty-two chess players, both expert and novice, compete in a dark room at sixteen closely-arranged tables. They use burning candles as chess pieces, imbuing the performance with a sense of danger and urgency.

As in Cage’s Reunion, Kaino has used indeterminacy to structure the performance. Each participant becomes a co-creator of the larger spectacle, choosing his or her moves, but is unable to control the outcome of their game or the performance as a whole. Just as the density of sound builds and diminishes over the course of Cage’s Reunion performance, so too does the amount of light during The Burning Boards. “Burning boards” is sometimes defined as the act of using fire to level a playing field.9 Here, the advantages of experts over novices are leveled, and the value of skill diminishes as the element of chance increases. Unidentifiable pieces cannot be played, nor can those burned out or stuck to the board. Soon players realize that they are battling their shared situation—the board and pieces, not each other. They can better survive through mutual accommodation than through zero-sum aggression. Competition gives way to comity and onerous constraints lead to comical, collegial outcomes.

Neither Reunion nor The Burning Boards were intended to be static historical events, but rather events to be periodically performed anew. Three years after Glenn Kaino first staged The Burning Boards, Cage’s Reunion was restaged for the first time since 1968 through the efforts of curator Sarah Robayo Sheridan in conjunction with Scotiabank Nuit Blanche. Performed in the same space as the original presentation, two of the chess players who participated were artists Dove Bradshaw and William Anastasi, the latter being a good friend of Cage who had played chess with him daily for many years. Kaino restaged The Burning Boards at the Haudenschild Garage in conjunction with Orange County Museum of Art’s Disorderly Conduct exhibition in the spring of 2008, bringing together some collaborators from the original performance, as well as new ones. The World Chess Hall of Fame is the first institution to host live performances of both of the events, drawing chess and art enthusiasts from near and far. With contributions by an open-ended array of collaborators, these artists’ works can continue to challenge and inspire the chess and cultural communities for generations to come.

—Larry List, Guest Curator, 2014

—

1 John Cage, interview by Adrienne Clarkson. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s The Day it Is. April 18, 1968. ©1968 Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. All rights reserved.

2 Ibid.

3 Margaret Leng Tan. Telephone conversation with author. New York City, 30 March, 2014. Verbatim description of Cage’s sense of indeterminacy as explained to the author by veteran performer of Cage’s piano works.

4 Ibid.

5 Accounts vary as to when the next day Cage and Teeny Duchamp completed their game, but all report that Teeny was triumphant. A sad note is that Reunion proved to be Marcel Duchamp’s last public appearance. He passed away quietly on October 1, 1968, at his home in Paris, France, after sharing a pleasant dinner with Teeny, old friends Man Ray and Robert Lebel and their wives.

6 Schonberg, Harold C. “Music: Libel on the Bishops and Pawns.” New York Times. May 28, 1968.

7 Projectile. “Glenn Kaino: Of Passed Pawns and Communicating Rooks.” November 10, 2005. (New York City, New York. Press release).

8 Ibid.

9 Rosario, Nelly. “Burning at the Boards,” The United States Chess Federation. http://www.uschess.org/content/blogcategory/19/80/ (June, 2007).

Participating Musicians: 1968 Reunion, Toronto

Central to the success of John Cage’s bold musical experiments, such as Reunion, were a small but brilliant group of musicians who shared his vision and with whom he worked repeatedly.

David Behrman (b. 1937) has distinguished himself in the realm of experimental music through his work as an artist, composer, and producer. In 1966, Behrman co-founded the Sonic Arts Union, a group of musicians who collaborated to create innovative music. During the 1960s, Behrman produced many of the albums in Columbia Records’ Music of Our Time series, which showcased the work of avant-garde musicians. In the years since, he has created sound and multimedia installations and has served on the faculty of the Milton Avery Graduate Arts Program at Bard College.

Lowell Cross (b. 1938) has been active in the realm of experimental music since the 1960s. Known for his work as both a composer and creator of instruments and multimedia installations, Cross invented the electronic chessboard used in the 1968 performance of Reunion. He, along with his collaborator Carson D. Jeffries, pioneered the technology for laser light shows, and staged the first public multicolor laser presentation in 1969. Cross, now Professor Emeritus in the School of Music at the University of Iowa, is also highly regarded for his writings about experimental music.

Gordon Mumma (b. 1935) is a composer, performer on French horn, and pioneer of electronic music. He became involved with the contemporary music scene while living in Ann Arbor, Michigan, from 1953–1966. There he co-founded the ONCE Festivals of Contemporary Music and the Cooperative Studio for Electronic Music. Mumma would go on to become a member of the Sonic Arts Union and serve as a composer-musician for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Since then, he has served on the faculty of numerous institutions, earned acclaim as a writer, and continued to compose and perform.

David Tudor (1926–1996) first achieved renown in the 1950s as a performer of avant-garde piano pieces. During the same decade, he met John Cage, with whom he would collaborate throughout his career. In the 1960s, Tudor, slowly ceased his work as a pianist, becoming known as a pioneer in the performance of live electronic music, often utilizing instruments of his own invention. He also created multimedia pieces which were exhibited in museums and galleries around the world. Tudor succeeded Cage as the Musical Director of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company following Cage’s death in 1992.

Participating Musicians: 2014 Gallery Installation

Many musicians of subsequent generations have great respect for John Cage and an intimate knowledge of his work and ideas. Fellow exhibitor and music producer Glenn Kaino has invited four diverse talents to produce digital music tracks to be mixed by the 2010 Reunion chess board while on display at the World Chess Hall of Fame.

Herb Alpert (b. 1935) has achieved fame through his work as a songwriter, producer, and performer. A 2006 inductee to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Alpert co-founded A&M Records, one of the most successful independent music companies, with Jerry Moss. He also formed Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass Band, one of the earliest groups to successfully fuse Latin American, jazz, and pop influences. In years since, he has found success as a solo performer and artist and created the Herb Alpert Foundation, a philanthropic organization.

Body/Head is the experimental duo of bassist Kim Gordon (b. 1953) and guitarist Bill Nace (b. 1977). Gordon is known as a co-founder of the iconic experimental band Sonic Youth and a performer in CKM and Free Kitten, as well as a visual artist and fashion designer. Nace performed previously with X.O.4, Ceylon Mange, and Vampire Belt. Since 2012, they have evolved from creating instrumental improvisations to producing increasingly complex works involving vocal elements. 2013 marked the release of their debut album, Coming Apart.

Mark Mothersbaugh (b. 1950) co-founded Devo, a legendary band that employed innovative musical techniques, a unique visual style, and technology. Their music, which integrated new wave and punk influences, wrapped criticism of American society in unconventional, ironic albums. Mothersbaugh has also attained acclaim as a composer for television and film, creating music for children’s shows including Rugrats and Pee Wee’s Playhouse, and scoring many films by director Wes Anderson, including The Royal Tenenbaums and The Life Aquatic, among numerous other projects.

YACHT is a conceptual pop group based in Los Angeles, California. It is the brainchild of Jona Bechtolt and Claire L. Evans, whose wide-ranging interests and deep-seated ADD cause YACHT to frequently metamorphose: from band to belief system, from disco infiltrators to punk rockers, from performance artists to graphic designers, publishers, sculptors, or philosophers.