A celebration of 16 World and 49 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame Inductees. View historical artifacts including books, photographs, chess sets, and more.

On View: March 9 - October 7, 2012

The World Chess Hall of Fame was created in 1986 by the United States Chess Federation and its president at the time, E. Stephen Doyle. Originally known as the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame, the museum opened in 1988 in the basement of the Federation's then headquarters in New Windsor, New York, with an exhibition featuring a book of chess openings signed by Bobby Fischer, the Paul Morphy silver set, and cardboard plaques honoring past grandmasters. In 1992, the U.S. Chess Trust purchased the museum and moved its contents to Washington D.C. From 1992 to 2001, the collection grew to include the World Chess Championship trophy won by the U.S. team in 1993, numerous chess sets and boards, and the U.S. and World Hall of Fame inductee plaques.

In 2001, the institution moved into a new, multi-million dollar facility at the Excalibur Electronics headquarters in Miami, Florida and was renamed the World Chess Hall of Fame and Sidney Samole Museum. As General Manager of Fidelity Electronics, Samole conceived of the first chess computer, Chess Challenger 1, in 1977, and the new museum’s name was a tribute to his pioneering work at the intersection of chess and modern technology. Under the leadership of Executive Director Al Lawrence, the museum continued collecting chess sets, books, tournament memorabilia, advertisements, photographs, furniture, medals, trophies, and journals until it closed in 2009.

Due to the vibrancy of Saint Louis and the growing international reputation of the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis, it was then proposed that the contents of the Miami institution be moved to Saint Louis. Realizing the potential to provide area youth with a vital educational resource, Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield provided seed funding to relocate the institution to Saint Louis. U.S. Chess Trust President Jim Eade, Mr. Sinquefield, and other staff and board members from both the Trust and the USCF approved the move in August 2010.

The World Chess Hall of Fame opened on September 9, 2011 in Saint Louis in the Central West End, a bustling neighborhood in the heart of the city. Housed in a 15,900 sqaure-foot residence-turned-business, the World Chess Hall of Fame is located directly across the street from the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis and features the U.S. and World Chess Halls of Fame, displays of artifacts from the permanent collection, and temporary exhibitions highlighting the great players, historic games, and rich cultural history of chess. The WCHOF partners with the Chess Club and Scholastic Center to provide innovative programming and outreach to local, national, and international audiences.

To learn more about the inductees to the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame click here.

To learn more about the inductees to the World Chess Hall of Fame click here.

Artifacts Featured in the Exhibition

Clips from the Documentary Bobby Fischer Against the World, 2011

This video includes several clips from the recent documentary, Bobby Fischer Against the World, directed by Liz Garbus, produced by Moxie Firecracker Films, and distributed by HBO Documentary Films. Harry Benson’s photographs of Bobby Fischer (many seen in the exhibition downstairs) were used to illustrate the documentary, and Benson is also interviewed several times throughout the film. In addition to the clips, several quotes from Harry Benson are included which were taken from Benson’s recent book, Bobby Fischer.

Signed Chess Board Flown on the Endeavor Space Shuttle

This chess board, signed by the 2010 U.S. and Women’s Chess Championship, was flown as part of the Official Flight Kit on the space shuttle Endeavor.

The mission—STS-134—named for the 134th space shuttle flight (and also the last U.S. space shuttle launch) carried a variety of objects from non-profits and schools to tour space.

During the 14-day mission, the STS-134 crew members, Commander Mark Kelly, Pilot Gregory H. Johnson, and Mission Specialists Michael Fincke, Greg Chamitoff, Andrew Feustel, and European Space Agency astronaut Roberto Vittori, took to the Space Station the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS) and spare parts including two S-band communications antennas, a high-pressure gas tank and additional spare parts for Dextre. This was the 36th shuttle mission to the International Space Station.

STS-134 launched on May 16 and returned on June 1, 2011 and had a total of four space walks.

The board was donated by the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis and is now in the permanent collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame. The 2010 U.S. Championship players included Varuzhan Akobian, Levon Altounian, Joel Benjamin, Vinay Bhat, Larry Christiansen, Jaan Ehlvest, Ben Finegold, Dmitry Gurevich, Robert Hess, Gregory Kaidanov, Gata Kamsky, Melikset Khachiyan, Jesse Kraai, Irina Krush, Sergey Kudrin, Alex Lenderman, Hikaru Nakamura, Ray Robson, Alexander Shabalov, Samuel Shankland, Yuri Shulman, Alexander Stripunsky, and Alex Yermolinsky.

The 2010 Women’s players included, Tatev Abrahamyan, Camilla Baginskaite, Sabina Foisor, Irina Krush, Beatriz Marinello, Abby Marshall, Alisa Melekhina, Alexander Onischuk, Katerina Rohonyan, Anna Zatonskih, and Iryna Zenyuk.

Boy Scouts of America Chess Merit Badge

On Saturday, September 10, 2011, the World Chess Hall of Fame and the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis hosted the launching of the Boy Scouts of America Chess Merit Badge. Twenty scouts earned the brand-new badge from merit badge counselor and founder of the Chess Club, Jeanne Sinquefield and the special guest, NASA Astronaut Greg Chamitoff, passed out the award to 15 of the scouts who were able to attend the event.

The day’s events included a human chess match played by local scouts, which depicted the most recent Earth verus Space match hosted on uschess.org/nasa2011. The original game was was declared a win for Earth after 22 moves, but the new finale, as reinterpreted by GM Yasser Seirawan and WGM Jennifer Shahade, played the game out to a draw.

In addition to the honor of having Greg Chamitoff as a special guest and awarding Chess Merit Badges to the scouts, he also presented a chessboard that flew with him on the last launch of the Endeavor Space Shuttle during Mission STS-134, currently seen on display at the World Chess Hall of Fame.

Requirements for achieving the Chess Merit Badge include things such as learning scorekeeping using the algebraic system of chess notation and explaining the four rules for castling. Additionally, Scouts must teach someone else how to play chess, play in a chess tournament, or organize a competition. For more information about the Chess Merit Badge visit the Boy Scouts of America website here. You can also learn about the Chess Merit Badge requirements by clicking here to visit the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis’ website. Pamphlets are available for sale at the World Chess Hall of Fame and the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis.

Sports Illustrated and Chess Life Articles

Left: Sports Illustrated, August 14, 1972

Right: Chess Life, March 2008

Sports Illustrated – August 14, 1972

This article, entitled “How to Cook a Russian Goose” discusses the match following Game 11 of the best-of-24 series. In addition, it continues to address Fischer’s poor manners and the trouble he had caused before and throughout the match. The article states, “While the chess proceeded sporadically, the Icelanders grew increasingly annoyed by Fischer’s early dyntir, meaning nonsense. Attendance dropped from some 2,500 at the first game to around 900 or less in the last two. A newspaper letter writer had referred to Fischer as the most hated man in Iceland.” The article, in its entirety, is located in the bin on the north wall of this exhibition.

Chess Life – March 2008 (right)

Upon the death of Bobby Fischer (January 17, 2008), Chess Life published an edition with a look at Bobby’s life by GM Larry Evans as well as an in-depth timeline and quotes by and about Fischer, organized by Al Lawrence. The latter contains a tribute by Dr. Frank Brady, president of the Marshall Chess Club and author of Fischer’s most famous biography Profile of a Prodigy and the recent Endgame, “Bobby Fischer’s passing alters the Zeitgeist of chess. He was more than iconic. He was chess. Last month I gave a speech at the Marshall Chess Club, 'Bobby Fischer: The Pride and Sorrow of Chess,' and Bobby saw it on YouTube. He made nostalgic reference to it through an intermediary, as if he was somehow reaching out after all of these years. I asked him, through the Internet to come back to the United States, face the charges leveled against him (they undoubtedly would have been dismissed), pay his back taxes, and get on with his chess life. Little did I know he was on his deathbed. As outré as he was, the chess world will miss Bobby Fischer. Strangely, I will too.”

Fischer vs. Spassky Champion Chessmate Game

Created in 1972, this learning tool featured all 20 games of the 1972 World Championship and was designed to double as a teaching device and a “souvenir” of the Championship.

LIFE Magazine and John W. Collins' My Seven Chess Prodigies

Front: LIFE, February 21, 1964

Back: My Seven Chess Prodigies by John W. Collins, 1974

LIFE, February 21, 1964

The article “One Track Mastermind” ironically begins by discussing how a 20-year-old Bobby Fischer had a difficult time beating Tigran Petrosian, who he beat in 1971 to qualify for the 1972 World Chess Championship.” The article, in its entirety, is located in the bin on the north wall of this exhibition.

My Seven Chess Prodigies by John W. Collins, 1974

John (Jack) Collins was coach to many well-known chess players (many of whom are in the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame), including Bobby Fischer, Raymond Weinstein, Robert Byrne, William Lombardy, Donald Byrne, Lewis Cohen, and Salvatore Matera. The set, board, and clock that Fischer and these other youths trained on are also on display in this exhibition.

This copy is signed by Bobby Fischer and was given to his then-girlfriend Zita Rajcsanyi, a young Hungarian chess master.

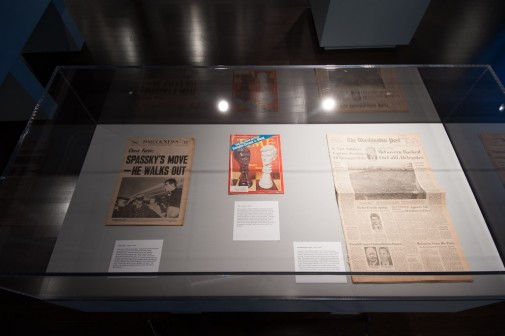

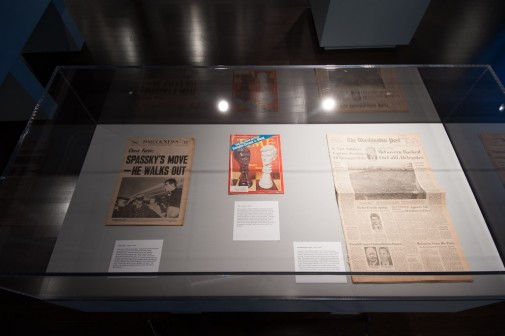

Daily News, Time Magazine, and The Washington Post

Left: Daily News, July 5, 1972

Center: Time, July 31, 1972

Right: The Washington Post, July 6, 1972

Daily News, July 5, 1972

This July 5, 1972 article entitled, “Anybody for Chess? Nyet Yet” discusses the issues of the delay of the World Chess Championship on both the part of Fischer and Spassky. Spassky became outraged with Fischer's demands and launched his counterattack with a stern protest, some sharp criticism, a walkout, and a demand for two-day postponement of the start of the match. Max Euwe, president of the International Chess Federation, said: “When Spassky is here Fischer doesn’t come. As soon as Fischer comes, Spassky runs away.”

Time, July 31, 1972

This cover story entitled “The Battle of the Brains” continues the discussion of Fischer and his socially-awkward behavior. U.S. Grandmaster Larry Evans (who is in the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame and can be seen in clips of Bobby Fischer Against the World) states, “To those who know him best, Bobby was merely being Bobby. He is the most individualistic, intransigent, uncommunicative, uncooperative, solitary, self-contained and independent chess master of all time, the loneliest chess champion in the world. He is also the strongest player in the world. In fact, the strongest player who ever lived.”

The Washington Post, July 6, 1972

This July 6, 1972 article entitled, “Fischer Extends Apology, Soviets Accept but Chess Match Date in Doubt” contains Bobby Fischer’s official apology for delaying the World Chess Championship. “We are sorry the world championship has been delayed. My problems were not with Spassky whom I respect as a man and admire as a player. If grandmaster Spassky or the Soviet people were distressed or discomfited, I am unhappy for I had not the slightest intention of this occurring,” Fischer said. Max Euwe, the then-president of the International Chess Federation condemned Fischer’s behavior of the last several months as the inexcusable—“there isn’t anyone in this locality who would not condemn him.”

Beginners Chess By Bobby Fischer, 1966

Bobby Fischer generally refused to allow his name to be used for endorsements of any kind, so it was quite unusual that he allowed this Milton Bradley beginner’s chess game to do so.

Issues of LIFE Magazine

Left: LIFE, May 19, 1972

Center: LIFE, November 12, 1971

Right: LIFE, July 28, 1972

LIFE, May 19, 1972

This edition contains the article “Chess Champion Bobby Fischer is Deep in Training” by Brad Darrach with photos by Harry Benson. Several of the photos seen in this article were taken during Bobby’s training period at the Grossinger’s Resort in upstate New York and can be seen in the second floor exhibition. The article, in its entirety, is located in the bin on the north wall of this exhibition.

LIFE, November 12, 1971

This edition contains the article “Bobby Fischer is a Ferocious Winner” written by Brad Darrach with photos by Harry Benson. Several of the photos seen in this article, including the cover shot are on display on the second floor exhibition. The article, in its entirety, is located in the bin on the north wall of this exhibition.

LIFE, July 28, 1972

This edition contains the two-page spread entitled, “The Sweet Rose of Victory” featuring two photographs by Harry Benson, one of which is on display on the second floor exhibition.

Chess set from 1972 World Chess Championship Game 3 with a chess board autographed by Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky

Game 3 of the 1972 World Chess Championship has been considered to be the turning point of the match. After losing Game 1, Fischer did not show up for Game 2 and demanded that Game 3 be played in a small room, backstage away from cameras. At the last minute, Spassky agreed and was beaten by Fischer for the first time ever. Fischer played the ultra-sharp Benoni with the double-edged novelty 11...Nh5. The rest of the games were returned to the main stage but without cameras at the demand of Fischer. This set was used in Game 3.

Notation for Game 3:

|

1. d4 Nf6

2. c4 e6

3. Nf3 c5

4. d5 exd5

5. cxd5 d6

6. Nc3 g6

7. Nd2 Nbd7

8. e4 Bg7

9. Be2 O-O

10. O-O Re8

11. Qc2 Nh5

12. Bxh5 gxh5

13. Nc4 Ne5

14. Ne3 Qh4

15. Bd2 Ng4

16. Nxg4 hxg4

17. Bf4 Qf6

18. g3 Bd7

19. a4 b6

20. Rfe1 a6

|

21. Re2 b5

22. Rae1 Qg6

23. b3 Re7

24. Qd3 Rb8

25. axb5 axb5

26. b4 c4

27. Qd2 Rbe8

28. Re3 h5

29. R3e2 Kh7

30. Re3 Kg8

31. R3e2 Bxc3

32. Qxc3 Rxe4

33. Rxe4 Rxe4

34. Rxe4 Qxe4

35. Bh6 Qg6

36. Bc1 Qb1

37. Kf1 Bf5

38. Ke2 Qe4+

39. Qe3 Qc2+

40. Qd2 Qb3

41. Qd4 Bd3+ 0-1

|

Halldór Pétursson

Postcards and Drawings from the 1972 World Chess Championship

Countless commemorative items were made to celebrate the 1972 World Chess Championship in Reykjavik, Iceland. Some of the most famous items created were caricatures of Fischer and Spassky by the famous Icelandic cartoonist Halldór Pétursson. Seen here is the entire series of postcards, 18 in total, as well as two colored drawings based on those cards.

Pétursson (1916-1977) received a degree in commercial graphics in 1938 from a school in Copenhagen. From 1942-45, he studied at the Minneapolis School of Art and the Arts Students League in New York.

LIFE Magazines and 1972 World Chess Championship Commemorative Objects

Left: LIFE, August 11, 1972

Center: 1972 World Chess Championship Commemorative Objects

Right: LIFE, July 21, 1972

LIFE, August 11, 1972 (left)

This edition contains the article “Bobby is Not a Nasty Kid” by Brad Darrach with photos by Harry Benson. These photographs were taken in Reykjavík, Iceland during the 1972 World Chess Championship and many are on display on the second floor exhibition. This article, in its entirety, is located in the bin on the north wall of this exhibition.

1972 World Chess Championship Commemorative Objects (center)

Icelandic Chess Federation’s Official Commemorative Program

World Chess Championship Commemorative Medal

World Chess Championship Match ticket – Match 13

LIFE, July 21, 1972 (right)

This edition contains a one-page article entitled “Bobby and The Black Bishop’s Last Raid” and discusses Fischer losing Game 1 of the World Chess Championship. This photograph was taken by Harry Benson CBE.