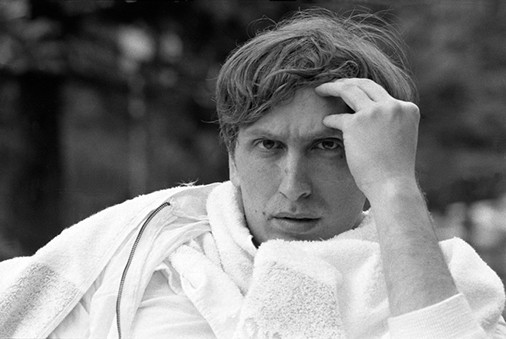

World-renowned photographer Harry Benson was the only person to have private access to Bobby Fischer during the entire 1972 World Chess Championship match in Reykjavík, Iceland. Benson captured intimate images of this time with Fischer and was the first person to deliver the news to Fischer that he had won the match.

On View: March 9 - October 7, 2012

Benson began photographing Fischer when on assignment for LIFE magazine in 1971. Sent to Buenos Aires, Argentina to cover the 1971 Candidates Tournament, Benson began to cultivate a relationship with Bobby, who was known for being notoriously camera-averse, guarded, and socially awkward. Being skeptical of journalists, Fischer would request late night meetings with Benson which generally consisted of quiet walks broken up by Fischer pulling out a pocket chess set to play under lampposts from time to time. Throughout the assignment, Benson and Fischer began to form a friendship and Benson noticed that Fischer seemed most comfortable in the company of animals and children, who also seemed exceedingly drawn to him. Fischer exuded a sense of patience and understanding with these groups that he did not possess with his peers, who he generally dismissed. Fischer defeated Tigran Petrosian at the Candidates Tournament, qualifying him for the World Chess Championship match. With this victory, he not only continued his rise among chess players, but also became a pop-culture sensation. At the height of the Cold War, the media played up the impending battle between the American and the Russian Boris Spassky, the defending World Chess Champion. News outlets referred to the upcoming match as the “Match of the Century” and used headlines such as “Fischer vs. Spassky: A Major Struggle in the Cold War.”

In an uncharacteristic twist, Fischer exclusively invited Benson and LIFE reporter Brad Darrach to visit him as he trained for the championship at Grossinger’s Resort in upstate New York. Considering himself an athlete, Fischer noted that playing chess required an enormous amount of stamina. He chose this resort complex in the Catskill Mountains due to its reputation as a popular training facility for sports legends such as Rocky Marciano and Jackie Robinson. In addition to his scrupulous chess study, Fischer followed a strict regimen of physical training including running, tennis, swimming, biking, jump rope, and hand strengthening exercises—the latter in an effort to “crush” the Russians and their dominance of the chess world.

The tales of the World Chess Championship in Reykjavík, Iceland in the summer of 1972 are numerous and fantastic. Fischer arrived late to the first game, forfeited Game 2, inspected television cameras and lights, insisting that they were making too much noise or contained devices that were intended to distract him, and had special chessboards created for the match. He made outrageous demands—requesting more money than the agreed-upon prize fund of $125,000 (to be split ⅝ for the winner and ⅜ for the loser), and requiring that Game 3 be played in a “back room” away from the agreed-upon setting. Much speculation surrounded this behavior and it was debated if this was “normal” Fischer conduct or if he was intentionally attempting to cause a psychological breakdown of his opponent.

The match was organized as the best of 24 games—wins would count as one point and draws as a half point, with the winner being the first to reach 12 ½ points. The first game took place on July 11th and the last game began on August 31st and was adjourned after 40 moves. Spassky resigned the next day without resuming play and the 29-year-old Fischer won the match 12 ½-8 ½, becoming the 11th World Chess Champion and the first American-born player to do so—ending 24 years of Soviet domination of the World Chess Championship.

Benson continued to cultivate a journalistic friendship with Fischer. The two spent many hours together during the nearly two months in Iceland, walking and talking night after night through the hills of the Icelandic countryside. Benson noted that the pressure on Fischer was enormous—it is known that Fischer received several phone calls from Henry Kissinger encouraging him to play the match when he threatened not to. Noticing Fischer’s lack of social skills and recognizing his loneliness and isolation, Benson stated, “Bobby regarded the press as enemies, yet there had to be one friendly face in the enemy camp, and I figured it might as well be me.”

As the images in this exhibition show, Benson’s photography captures a side of the elusive and controversial chess genius that is rarely seen, and offers a window into the private world of the man Benson calls "the most eccentric and most fascinating person I have ever photographed."